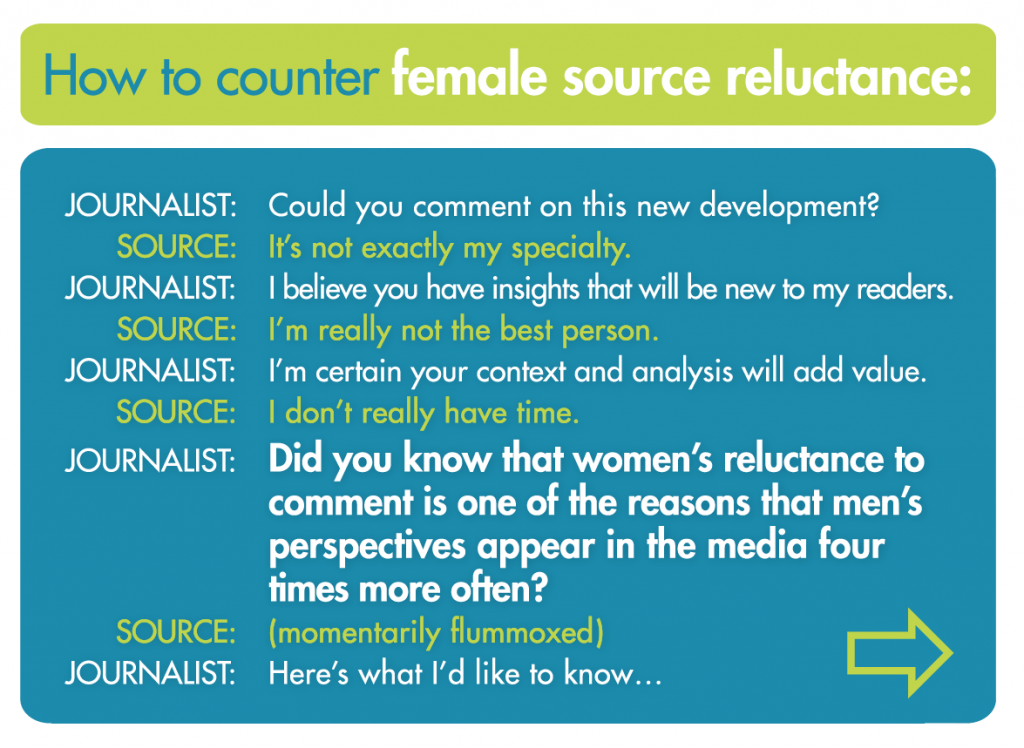

Why do women with demonstrated expertise decline media interviews? And how can you overcome their reluctance?

By Shari Graydon

Founder, Informed Opinions

For 10 years, the Canadian-based non-profit organization Informed Opinions has trained and motivated more than 2,500 women across sectors and fields to share their experience and education-informed insights with reporters, producers, and editors. Here's what we've learned about the sometimes elusive but often valuable woman expert:

1. She may be motivated more by impact than public profile.

Unlike some of her more readily available male colleagues, she may not crave the spotlight, but be more focused on ensuring she makes a difference on the ground.

SO: Make clear, if you can, the value of your story and her contribution to it. How many people are affected by this issue? How important is it that her insights are present to counter the “other side” or offer nuance and analysis that otherwise won’t be there? How big an audience will your story reach? What opportunity does this give her to shift views on something she cares about?

2. She knows she’ll be held to a higher standard of authority than her male colleagues.

(Watching how prominent female politicians are covered has taught her that.) Plus, even if she has a Ph.D. or 25 years of experience, she's often conscious of who else in her field might be better suited to address a specific topic, and may confess, “I’m not the best person.”

SO: Tell her that in your experience, there often is no single “best person,” that you need someone who can add value, and that – based on the knowledge she has – you believe she can provide insight that will help your audience better understand the issue.

3. She may or may not be aware of how under-represented women’s voices are, and the broader consequences of their absence.

SO: Tell her that you’re working to bridge the gender gap in your reporting so that the news media – and the policies and priorities they influence – reflect and account for the differing needs of women, children and many of society’s most vulnerable.

Remind her that news media have an extraordinary capacity to draw attention to an issue or cause, and to educate policymakers, to help bring about change. Let her know a media profile increases the likelihood that decision-makers or funders will return her phone calls, give money to her cause, and pass laws she supports.

4. She may be worried about being trolled online.

This is especially true if her area of expertise relates to partisan politics, controversial identity issues or hot-button issues like climate change and migration.

SO: Let her know the comment policy of your site or publication. Consider disabling anonymous comments on controversial identity issues. Acknowledge that she may be criticized for speaking up – especially if she’s advocating for society’s most vulnerable. But remind her that if women with the privileges of education and employment, safe housing and secure food are not prepared to step forward, what hope is there for those without?

5. She may be time-challenged.

Chances are she is as busy as the rest of us. She may have caregiving duties or community volunteer commitments on top of a demanding job. Her time is probably highly scheduled. As a result, agreeing to an interview may do serious collateral damage to the rest of her day.

SO: Ask how you can accommodate her participation. Offer to interview by phone or Skype. If she has children, invite her to bring them along, allowing them to sit in the greenroom. Can you shift the time and pre-tape the interview, or accommodate her schedule in some other way?

6. She may be intimidated by an unfamiliar world.

Source: Informed Opinions

Most people who are unfamiliar with a newsroom or who have little experiencing interacting with reporters and may find the prospect of an interview daunting. She may feel poorly equipped to effectively negotiate what’s required.

SO: Look for ways to demystify the process by offering tours of your studio or newsroom to viewers or readers – in person or online. Answer ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ on your site and provide the page link to prospective sources.

ALSO: Offer professional tips. Let her know if a TV clip will be edited, and that she can start again if she stumbles. Tell her in advance that concrete examples or analogies make an issue more interesting and relatable than theoretical descriptions. Tell her if she doesn't know the precise answer to a posed question but can bridge to something relevant, that's also useful.

7. She may believe that hours of preparation are necessary.

SO: Let her know if you only have room in your story for one 30-word quote. Tell her that reading the executive summary of the new study or report, versus all 12,000 words, will likely allow her to provide useful context. And if you need a longer on-air discussion, let her know where you want to take the conversation, so she has a chance to think of pertinent examples or look up relevant data points.

8. She may have had bad experiences with other reporters.

She may object to sensationalist headlines, irresponsible reporting, de-contextualized data or misleading quotes. And so she may resist risking her public reputation in what feels like a high stakes game where she has no control over the end product.

SO: Be deliberate about building trust by being clear about what your angle is if you have one, or your genuine curiosity and openness to being surprised if you don’t. If the interview is seeking context for a complex issue (vs. accountability from a person in power) offer to send questions in advance. This is likely to result in much better, clearer and more helpful responses. She can review the relevant research, note specific numbers, or identify an example that will help your audience understand the topic more easily. Alternatively, permit a source with complex or technical expertise to review her quotes before publication to ensure that you haven’t inadvertently introduced errors.

Source: Informed Opinions, Media Training for Women Experts

Acknowledge the need to make the issues accessible to a lay audience but assure her of your commitment to doing so responsibly. Mention your ombudsperson or public editor, if you have one.

ALSO: Consider inviting her written input, if your format allows. Let her answer by email or commission written commentary in her own words if she has a demonstrated capacity to translate her knowledge into accessible and engaging prose. The opportunity to reflect and check facts, to control the emphasis, and to incorporate nuance is sometimes irresistible.

FINALLY: Avoid framing the issue in black and white. Debate style programs that position a complex issue in simplistic and polarizing terms are often unappealing to thoughtful women.

9. She understands that television is a visual medium.

She knows that viewers often judge women based on their appearance. (And she’s probably her own harshest critic.)

SO: Let her know if your studio has a make-up artist or suggest a location with lighting that won’t add 30 years to her face. Let her know if her entire body will be in the frame, or just head and shoulders. If you’re calling several days in advance, volunteer information about what clothing and colors to choose or avoid.